Iraq

Republic of Iraq | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: مَوْطِنِيْ Mawṭinī "My Homeland" | |

.svg/250px-Iraq_(orthographic).svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Baghdad 33°20′N 44°23′E / 33.333°N 44.383°E |

| Official languages | |

| |

| Ethnic groups (1987)[3] | |

| Demonym(s) | Iraqi |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic |

| Abdul Latif Rashid | |

| Mohammed Shia' Al Sudani | |

| Legislature | Council of Representatives |

| Federation Council[4] (not yet convened)[5] | |

| Council of Representatives | |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 3 October 1932 | |

| 14 July 1958 | |

| 15 October 2005 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 438,317 km2 (169,235 sq mi) (58th) |

• Water (%) | 4.93 (as of 2024)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 82.7/km2 (214.2/sq mi) (125th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2012) | 29.5[9] low inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (128th) |

| Currency | Iraqi dinar (IQD) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +964 |

| ISO 3166 code | IQ |

| Internet TLD | |

Iraq,[a] officially the Republic of Iraq,[b] is a country in West Asia and a core country in the geopolitical region known as the Middle East. With a population of over 46 million, it is the 30th-most populous country. It is a federal parliamentary republic that consists of 18 governorates. Iraq is bordered by Turkey to the north, Saudi Arabia to the south, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and Kuwait to the southeast, Jordan to the southwest, and Syria to the west. The capital and largest city is Baghdad. Iraqi people are diverse; mostly Arabs, as well as Kurds, Turkmen, Yazidis, Assyrians, Armenians, Mandaeans, Persians and Shabakis with similarly diverse geography and wildlife. Most Iraqis are Muslims – minority faiths include Christianity, Yazidism, Zoroastrianism, Mandaeism, Yarsanism and Judaism.[11][3][12] The official languages of Iraq are Arabic and Kurdish; others also recognized in specific regions are Turkish, Suret, and Armenian.[13]

Starting as early as the 6th millennium BC, the fertile alluvial plains between Iraq's Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, referred to as the region of Mesopotamia, gave rise to some of the world's earliest cities, civilizations, and empires in Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria.[14] Mesopotamia was known as a "Cradle of Civilisation" that saw the inventions of a writing system, mathematics, timekeeping, a calendar, astrology, and a law code.[15][16][17] Following the Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia, Baghdad became the capital and the largest city of the Abbasid Caliphate, and during the period of the Islamic Golden Age, the city evolved into a significant cultural and intellectual center, and garnered a worldwide reputation for its academic institutions, including the House of Wisdom.[18] It was largely destroyed at the hands of the Mongol Empire in 1258 during the siege of Baghdad, resulting in a decline that would linger through many centuries due to frequent plagues and multiple successive empires including the Ottoman Empire, which ruled over the vilayets of Mosul, Baghdad and Basra, which forms today's Iraq.

Modern Iraq dates back to 1920, when a British-backed monarchy under Faisal was established, followed by an independent Kingdom in 1932. It was overthrown in 1958 by General Qasim, who established and ruled a republic until he was overthrown in 1963. Iraq was then ruled by brothers Abdul Salam Arif and Abdul Rahman Arif. The Ba'ath party took power in a 1968 coup, first led by Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and then by Saddam Hussein. Under Saddam, the country fought the Iran–Iraq War and the Gulf War. In 2003 United States-led coalition forces invaded and occupied Iraq, overthrowing Saddam's regime. The war continued as an insurgency and sectarian civil war, which lasted until 2011. Continuing discontent over Nouri al-Maliki's government led to protests, after which a coalition of Ba'athist and Sunni militants launched an offensive against the government, initiating full-scale war in Iraq. The climax of the campaign was an offensive in Northern Iraq by the Islamic State (ISIS) that marked the beginning of the rapid territorial expansion by the group, prompting an American-led intervention. Iran also intervened and expanded its influence through sectarian Khomeinist militias. By the end of 2017, ISIS had lost all its territory in Iraq. Post-war conflict continues at a lower scale to this day.[19][20]

Iraq is a federal parliamentary republic country. The president is the head of state, the prime minister is the head of government, and the constitution provides for two deliberative bodies, the Council of Representatives and the Council of Union. The judiciary is free and independent of the executive and the legislature.[21] Iraq is considered an emerging middle power[22] with a strategic location.[23] It is a founding member of the United Nations, the OPEC as well as of the Arab League, the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, Non-Aligned Movement, and the International Monetary Fund. The country has the 5th largest oil reserves in the world and is a leading center of oil and gas industry. In addition, Iraq is an agricultural country where farming remains a vital sector of the country’s economy.[24] Since its independence, Iraq has experienced spells of significant economic and military growth and briefer instability including wars. Tourism in Iraq stands to be a major growth sector, including archaeological tourism and religious tourism[25] while the country is also considered to be a potential location for ecotourism.[26][27][28] The country is putting efforts to rebuild after the war with foreign support.[29][30][31]

Name

There are several suggested origins for the name. One dates to the Sumerian city of Uruk and is thus ultimately of Sumerian origin.[32][33] Another possible etymology for the name is from the Middle Persian word erāq, meaning "lowlands."[34] An Arabic folk etymology for the name is "deeply rooted, well-watered; fertile".[35]

During the medieval period, there was a region called ʿIrāq ʿArabī ("Arabian Iraq") for Lower Mesopotamia and ʿIrāq ʿAjamī ("Persian Iraq"),[36] for the region now situated in Central and Western Iran.[36] The term historically included the plain south of the Hamrin Mountains and did not include the northernmost and westernmost parts of the modern territory of Iraq.[37] Prior to the middle of the 19th century, the term Eyraca Arabica was commonly used to describe Iraq.[38][39]

The term Sawad was also used in early Islamic times for the region of the alluvial plain of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

As an Arabic word, عراق ʿirāq means "hem", "shore", "bank", or "edge", so that the name by folk etymology came to be interpreted as "the escarpment", such as at the south and east of the Jazira Plateau, which forms the northern and western edge of the "al-Iraq arabi" area.[40]

The Arabic pronunciation is [ʕiˈrɑːq]. In English, it is either /ɪˈrɑːk/ (the only pronunciation listed in the Oxford English Dictionary and the first one in Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary[41]) or /ɪˈræk/ (listed first by MQD), the American Heritage Dictionary,[42] and the Random House Dictionary.[43]

When the British established the Hashemite king on 23 August 1921, Faisal I of Iraq, the official English name of the country changed from Mesopotamia to the endonymic Iraq.[44] Since January 1992, the official name of the state is "Republic of Iraq" (Jumhūriyyat al-ʿIrāq), reaffirmed in the 2005 Constitution.[45][46][47]

History

Prehistoric and ancient Mesopotamia

Between 65,000 BC and 35,000 BC, northern Iraq was home to a Neanderthal culture, archaeological remains of which have been discovered at Shanidar Cave[50] This region is also the location of a number of pre-Neolithic burials, dating from approximately 11,000 BC.[51] Since approximately 10,000 BC, Iraq, together with a large part of the Fertile Crescent, was a centre of a Neolithic culture known as Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), where agriculture and cattle breeding appeared for the first time. In Iraq, this period has been excavated at sites like M'lefaat and Nemrik 9. The following Neolithic period, PPNB, is represented by rectangular houses. At the time of the pre-pottery Neolithic, people used vessels made of stone, gypsum and burnt lime (Vaisselle blanche). Finds of obsidian tools from Anatolia are evidences of early trade relations. Further important sites of human advancement were Jarmo (circa 7100 BC),[51] a number of sites belonging to the Halaf culture, and Tell al-'Ubaid, the type site of the Ubaid period (between 6500 BC and 3800 BC).[52] The respective periods show ever-increasing levels of advancement in agriculture, tool-making and architecture.

The "Cradle of Civilisation" is a common term for the area comprising modern Iraq as it was home to the earliest known civilisation, the Sumerian civilisation, which arose in the fertile Tigris-Euphrates river valley of southern Iraq in the Chalcolithic (Ubaid period).[53] It was there, in the late 4th millennium BC, that the world's first known writing system emerged. The Sumerians were also the first known to harness the wheel and create city states; their writings record the first known evidence of mathematics, astronomy, astrology, written law, medicine and organised religion.[53] The Sumerian language is a language isolate. The major city states of the early Sumerian period were Eridu, Bad-tibira, Larsa, Sippar, Shuruppak, Uruk, Kish, Ur, Nippur, Lagash, Girsu, Umma, Hamazi, Adab, Mari, Isin, Kutha, Der and Akshak.[53] The cities to the north like Ashur, Arbela (modern Erbil) and Arrapha (modern Kirkuk) were also extant in what was to be called Assyria from the 25th century BC; however, at this stage, they were Sumerian-ruled administrative centres.

During the Bronze Age, in the 26th century BC, Eannatum of Lagash created a short-lived empire. Later, Lugal-Zage-Si, the priest-king of Umma, overthrew the primacy of the Lagash dynasty in the area, then conquered Uruk, making it his capital, and claimed an empire extending from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean.[54] It was during this period that the Epic of Gilgamesh originates, which includes the tale of The Great Flood. The origin and location of Akkad remain unclear. Its people spoke Akkadian, an East Semitic language.[55] Between the 29th and 24th centuries BC, a number of kingdoms and city states within Iraq began to have Akkadian speaking dynasties, including Assyria, Ekallatum, Isin and Larsa. However, the Sumerians remained generally dominant until the rise of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2124 BC), based in the city of Akkad in central Iraq. Sargon of Akkad founded the empire, conquered all of the city states of southern and central Iraq, and subjugated the kings of Assyria, thus uniting the Sumerians and Akkadians in one state. The Akkadian Empire was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer.

.jpg/180px-Sargon_of_Akkad_(frontal).jpg)

He then set about expanding his empire, conquering Gutium, Elam in modern-day Iran, and had victories that did not result into a full conquest against the Amorites and Eblaites of the Levant. The empire of Akkad likely fell in the 22nd century BC, within 180 years of its founding, ushering in a "Dark Age" with no prominent imperial authority until the Third Dynasty of Ur. The region's political structure may have reverted to the status quo ante of local governance by city-states.[56] After the collapse of the Akkadian Empire in the late 22nd century BC, the Gutians occupied the south for a few decades, while Assyria reasserted its independence in the north. Most of southern Mesopotamia was again united under one ruler during the Ur III period, most notably during the rule of the prolific king Shulgi. His accomplishments include the completion of construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father Ur-Nammu.[57] In 1792 BC, an Amorite ruler named Hammurabi came to power and immediately set about building Babylon into a major city, declaring himself its king. Hammurabi conquered southern and central Iraq, as well as Elam to the east and Mari to the west, then engaged in a protracted war with the Assyrian king Ishme-Dagan for domination of the region, creating the short-lived Babylonian Empire. He eventually prevailed over the successor of Ishme-Dagan and subjected Assyria and its Anatolian colonies. By the middle of the eighteenth century BC, the Sumerians had lost their cultural identity and ceased to exist as a distinct people.[58][59]

It is from the period of Hammurabi that southern Iraq came to be known as Babylonia, while the north had already coalesced into Assyria hundreds of years before. However, his empire was short-lived, and rapidly collapsed after his death, with both Assyria and southern Iraq, in the form of the Sealand Dynasty, falling back into native Akkadian hands.

_(32577951406).jpg/220px-A_lion_on_the_Ishtar_Gate_of_Babylon_reconstructed_with_original_bricks_at_the_Pergamon_Museum_in_Berlin_575_BCE_(3)_(32577951406).jpg)

After this, another foreign people, the Language Isolate speaking Kassites, seized control of Babylonia. Iraq was from this point divided into three polities: Assyria in the north, Kassite Babylonia in the south central region, and the Sealand Dynasty in the far south. The Sealand Dynasty was finally conquered by Kassite Babylonia circa 1380 BC. The origin of the Kassites is uncertain.[60]

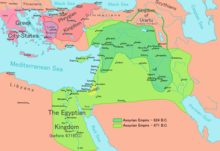

The Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BC) saw Assyria rise to be the most powerful nation in the known world. Beginning with the campaigns of Ashur-uballit I, Assyria destroyed the rival Hurrian-Mitanni Empire, annexed huge swathes of the Hittite Empire for itself, annexed northern Babylonia from the Kassites, forced the Egyptian Empire from the region, and defeated the Elamites, Phrygians, Canaanites, Phoenicians, Cilicians, Gutians, Dilmunites and Arameans. At its height, the Middle Assyrian Empire stretched from The Caucasus to Dilmun (modern Bahrain), and from the Mediterranean coasts of Phoenicia to the Zagros Mountains of Iran. In 1235 BC, Tukulti-Ninurta I of Assyria took the throne of Babylon.

During the Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BC), Babylonia was in a state of chaos, dominated for long periods by Assyria and Elam. The Kassites were driven from power by Assyria and Elam, allowing native south Mesopotamian kings to rule Babylonia for the first time, although often subject to Assyrian or Elamite rulers. However, these Akkadian kings were unable to prevent new waves of West Semitic migrants entering southern Iraq, and during the 11th century BC Arameans and Suteans entered Babylonia from The Levant, and these were followed in the late 10th to early 9th century BC by the Chaldeans.[61] However, the Chaldeans were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia.[62]

Iron Age

After a period of comparative decline in Assyria, it once more began to expand with the Neo Assyrian Empire (935–605 BC). Because of its geopolitical dominance and ideology based in world domination, the Neo-Assyrian Empire is by many researchers regarded to have been the first world empire.[63][64] At its height, the empire was the strongest military power in the world.[65] and ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as portions of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia. Under rulers such as Adad-Nirari II, Ashurnasirpal, Shalmaneser III, Semiramis, Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon II, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal, Iraq became the centre of an empire stretching from Persia, Parthia and Elam in the east, to Cyprus and Antioch in the west, and from The Caucasus in the north to Egypt, Nubia and Arabia in the south.[66]

It was during this period that an Akkadian-influenced form of Eastern Aramaic was adopted by the Assyrians as their lingua franca, and Mesopotamian Aramaic began to supplant Akkadian as the spoken language of the general populace of both Assyria and Babylonia. The descendant dialects of this tongue survive amongst the Mandaeans of southern Iraq and Assyrians of northern Iraq. The Arabs and the Chaldeans are first mentioned in written history (circa 850 BC) in the annals of Shalmaneser III.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire left a legacy of great cultural significance. The political structures established by the Neo-Assyrian Empire became the model for the later empires that succeeded it and the ideology of universal rule promulgated by the Neo-Assyrian kings inspired similar ideas of rights to world domination in later empires. The Neo-Assyrian Empire became an important part of later folklore and literary traditions in northern Mesopotamia. Judaism, and thus in turn also Christianity and Islam, was profoundly affected by the period of Neo-Assyrian rule; numerous Biblical stories appear to draw on earlier Assyrian mythology and history and the Assyrian impact on early Jewish theology was immense. Although the Neo-Assyrian Empire is prominently remembered today for the supposed excessive brutality of the Neo-Assyrian army, the Assyrians were not excessively brutal when compared to other civilizations.[67][68] In the late 7th century BC, the Assyrian Empire tore itself apart with a series of brutal civil wars, weakening itself to such a degree that a coalition of its former subjects, the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Parthians, Scythians and Cimmerians, were able to attack Assyria, finally bringing its empire down by 605 BC.[69]

The short-lived Neo-Babylonian Empire (620–539 BC) succeeded that of Assyria. It failed to attain the size, power or longevity of its predecessor; however, it came to dominate The Levant, Canaan, Arabia, Israel and Judah, and to defeat Egypt. Initially, Babylon was ruled by the Chaldeans, who had migrated to the region in the late 10th or early 9th century BC. Its greatest king, Nebuchadnezzar II, rivalled Hammurabi as the greatest king of Babylon. However, by 556 BC, the Chaldeans had been deposed by the Assyrian-born Nabonidus and his son and regent Belshazzar.[citation needed]

The transfer of empire to Babylon marked the first time the city, and southern Mesopotamia in general, had risen to dominate the Ancient Near East since the collapse of Hammurabi's Old Babylonian Empire. The period of Neo-Babylonian rule saw unprecedented economic and population growth and a renaissance of culture and artwork. Nebuchadnezzar II succeeded Nabopolassar in 605 BC. The empire Nebuchadnezzar inherited was among the most powerful in the world, in which he quickly reinforced his father's alliance with the Medes by marrying Cyaxares's daughter or granddaughter, Amytis. Some sources suggest that the famous Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, were built by Nebuchadnezzar for his wife (though the existence of these gardens is debated). Nebuchadnezzar's 43-year reign would bring with it a golden age for Babylon, which was to become the most powerful kingdom in the Middle East.[70] In the 6th century BC, Cyrus the Great of neighbouring Persia defeated the Neo-Babylonian Empire at the Battle of Opis and Mesopotamia was subsumed into the Achaemenid Empire. The Achaemenids made Babylon their main capital. The Chaldeans disappeared at around this time, though both Assyria and Babylonia endured and thrived under Achaemenid rule (see Achaemenid Assyria). Their kings retained Assyrian Imperial Aramaic as the language of empire, together with the Assyrian imperial infrastructure, and an Assyrian style of art and architecture.[citation needed]

In the late 4th century BC, Alexander the Great conquered the region, putting it under Hellenistic Seleucid rule for over two centuries.[71] The Parthians (247 BC – 224 AD) from Persia conquered the region during the reign of Mithridates I of Parthia (r. 171–138 BC). From northwestern Mesopotamia, the Romans invaded western parts of the region several times, and for over four centuries they ruled part of it, that were incorporated into the Mesopotamia province, until it was conquered by the Muslims in the 7th century. For a short period they also ruled Assyria, which was incorporated into the Assyria Provincia.[72][73]

Christianity began to take hold in Iraq (particularly in Assyria) between the 1st and 3rd centuries, and Assyria became a centre of Syriac Christianity, the Church of the East and Syriac literature. A number of independent states evolved in the north during the Parthian era, such as Adiabene, Assur, Osroene and Hatra.[citation needed] The Sassanids of Persia under Ardashir I destroyed the Parthian Empire and conquered the region in 224 AD. During the 240s and 250s AD, the Sassanids gradually conquered the independent states, culminating with Assur in 256 AD. The region became the frontier and battleground between the Sassanid Empire and Byzantine Empire.[citation needed]

Middle Ages

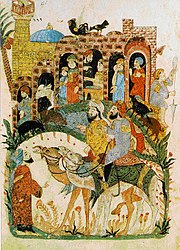

The first organised conflict between invading Arab-Muslim forces and occupying Sassanid domains in Mesopotamia seems to have been in 634, when the Arabs were defeated at the Battle of the Bridge. This was followed by Khalid ibn al-Walid's successful campaign which saw all of Iraq come under Arab rule within a year, with the exception of the Sassanid Empire's capital, Ctesiphon. By the end of 638, the Muslims had conquered all of the Western Sassanid provinces (including modern Iraq), and the last Sassanid Emperor, Yazdegerd III, had fled to central and then northern Persia, where he was killed in 651.[citation needed]

The Islamic expansions constituted the largest of the Semitic expansions in history. These new arrivals established two new garrison cities, at Kufa, near ancient Babylon, and at Basra in the south and established Islam in these cities, while the north remained largely Assyrian and Christian in character.[citation needed] The Abbasid Caliphate built the city of Baghdad along the Tigris in the 8th century as its capital, and the city became the leading metropolis of the Arab and Muslim world. Baghdad was the largest multicultural city of the Middle Ages, peaking at a population of more than a million,[74] and was the centre of learning during the Islamic Golden Age. The Mongols destroyed the city and burned its library during the siege of Baghdad in the 13th century.[75] In 1257, Hulagu Khan besieged Baghdad, sacked the city and massacred many of the inhabitants.[76] Estimates of the number of dead range from 200,000 to a million.[77]

The Mongols destroyed the Abbasid Caliphate and Baghdad's House of Wisdom. The city has never regained its previous pre-eminence as a major centre of culture and influence. Some historians believe that the Mongol invasion destroyed much of the irrigation infrastructure that had sustained Mesopotamia for millennia. Other historians point to soil salination as the culprit in the decline in agriculture.[78]

The mid-14th-century Black Death ravaged much of the Islamic world.[79] The best estimate for the Middle East is a death rate of roughly one-third.[80] In 1401, a warlord of Mongol descent, Tamerlane (Timur Lenk), invaded Iraq. After the capture of Baghdad, 20,000 of its citizens were massacred.[81] Timur also conducted massacres of the indigenous Assyrian Christian population, hitherto still the majority population in northern Mesopotamia, and it was during this time that the ancient Assyrian city of Assur was finally abandoned.[82]

Portuguese and Ottoman Iraq

During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Black Sheep Turkmen ruled the area now known as Iraq. In 1466, the White Sheep Turkmen took control. From 1508, as with all territories of the former White Sheep Turkmen, Iraq fell into the hands of the Iranian Safavids. With the Treaty of Zuhab in 1639, most of the territory of present-day Iraq came under the control of Ottoman Empire as the eyalet of Baghdad as a result of wars with the neighbouring rival, Safavid Iran. Throughout most of the period of Ottoman rule (1533–1918), the territory of present-day Iraq was a battle zone between the rival regional empires and tribal alliances.

In 1523, the Portuguese commanded by António Tenreiro crossed from Aleppo to Basra trying to make alliances with local lords in the name of the Portuguese king.[83] In 1550, the local kingdom of Basra and tribal rulers relied on the Portuguese against the Ottomans, after which the Portuguese threatened several times to invoke an invasion and conquest of Basra. From 1595, the Portuguese acted as military protectors of Basra,[84] and in 1624 they helped the Ottoman pasha of Basra to repel a Persian invasion. The Portuguese were granted a share of customs revenue and exemption from tolls. From approximately 1625 to 1668, Basra and the Delta marshes were in the hands of local chiefs independent of the Ottoman administration in Baghdad.[85] In the 17th century, the frequent conflicts with the Safavids had sapped the strength of the Ottoman Empire and had weakened its control over its provinces. The nomadic population swelled with the influx of bedouins from Najd. Bedouin raids on settled areas became impossible to curb.[86]

During the years 1747–1831, Iraq was ruled by a Mamluk dynasty of Georgian[87] origin who succeeded in obtaining autonomy from the Ottoman Porte, suppressed tribal revolts, curbed the power of the Janissaries, restored order and introduced a programme of modernisation of economy and military. In 1802, Wahhabis from Najd attacked Karbala in Iraq, killing up to 5,000 people and plundering the Imam Husayn Shrine.[88] In 1831, the Ottomans managed to overthrow the Mamluk regime and imposed their direct control over Iraq. The population of Iraq, estimated at 30 million in 800 AD, was only 5 million at the start of the 20th century.[89]

During World War I, the Ottomans sided with Germany and the Central Powers. In the Mesopotamian campaign against the Central Powers, British forces invaded the country and initially suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Turkish army during the Siege of Kut (1915–1916). However, the British began to gain the upper hand, and were further aided by the support of local Arabs and Assyrians. In 1916, the British and French made a plan for the post-war division of West Asia under the Sykes-Picot Agreement.[90] British forces regrouped and captured Baghdad in 1917, and defeated the Ottomans. An armistice was signed in 1918.

Mandate of Mesopotamia and independent kingdom

During the Ottoman Empire, Iraq was made up of three provinces, called vilayets in the Ottoman language:— Mosul Vilayet, Baghdad Vilayet, and Basra Vilayet, having distinct ethnic and religious groups. Following the partition of the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th century following WW1, these three provinces were joined into one kingdom after the region became a League of Nations mandate, administered by the British, under the name "State of Iraq". A fourth province (Zor Sanjak), which Iraqi nationalists considered part of Upper Mesopotamia was ultimately added to Syria.[91][92]

In line with their "Sharifian Solution" policy, the British established a monarchy on 23 August 1921, with Faisal I of Iraq as king, who was previously King of Syria, but was forced out by the French. The official English name of the country simultaneously changed from Mesopotamia to the endonymic Iraq.[44] Likewise, British authorities selected Sunni Arab elites from the region for appointments to government and ministry offices.[specify][93][page needed][94] The royal family were Hashemites, who were also rulers of neighboring Emirate of Transjordan, which later became the Kingdom of Jordan.[93] During the rise of Zionist movement and Arab nationalism, Faisal had a dream of a federation, consisting the modern states of Iraq, Lebanon, Syria and Palestine, including both modern Palestine and Israel.[95] He also signed Faisal–Weizmann agreement.

Faced with spiralling costs and influenced by the public protestations of the war hero T. E. Lawrence,[96] Britain replaced Arnold Wilson in October 1920 with a new Civil Commissioner, Sir Percy Cox.[97] Cox managed to quell a rebellion and was also responsible for implementing the policy of close co-operation with Iraq's Sunni minority.[98] Slavery was abolished in Iraq in the 1920s.[99] Britain granted independence to the Kingdom of Iraq in 1932,[100] on the urging of King Faisal, though the British retained military bases and local militia in the form of Assyrian Levies. King Ghazi ruled as a figurehead after King Faisal's death in 1933. His rule, which lasted until his death in 1939, was undermined by numerous attempted military coups, until his death in 1939. His underage son, Faisal II succeeded him, with 'Abd al-Ilah as Regent.[citation needed] On 1 April 1941, Rashid Ali al-Gaylani and members of the Golden Square staged a coup d'état. During the subsequent Anglo-Iraqi War, the United Kingdom invaded Iraq for fear that the government might cut oil supplies to Western nations because of his links to the Axis powers.

The war started on 2 May, and the British, together with loyal Assyrian Levies,[101] defeated the forces of Al-Gaylani, forcing an armistice on 31 May.[citation needed] Nuri Said served as the prime minister during the Kingdom of Iraq from 1930 to 1932. In 1930, during his first term, he signed the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, which, as a step toward greater independence, granted Britain the unlimited right to station its armed forces in and transit military units through Iraq and also gave legitimacy to British control of the country's oil industry. In addition, Said contributed to the establishment of the Kingdom of Iraq and the Iraqi army.[citation needed] The military occupation was followed by the restoration of the pre-coup government of the Hashemite monarchy. The occupation ended on 26 October 1947, although Britain was to retain military bases in Iraq until 1954, after which the Assyrian militias were disbanded. The rulers during the occupation and the remainder of the Hashemite monarchy were Nuri as-Said, the autocratic Prime Minister and 'Abd al-Ilah, the former Regent who now served as an adviser to King Faisal II.[citation needed] In 1958, Jordan's King Hussein formed a federation with Iraq, known as the Arab Federation.[102]

Iraqi Republic

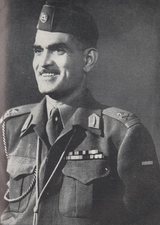

In 1958, the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown in the 14 July Revolution, which was led by the Brigadier General and nationalist Abd al-Karim Qasim.[103][104] This revolution was strongly anti-imperial and anti-monarchical in nature and had strong socialist elements.[105] Numerous people were killed in the coup, including King Faysal II, Prince Abd al-Ilah, and prime minister Nuri al-Sa'id, as well as the members of the royal family, which came to known as "the Royal family massacre".[102] After burial, their bodies were dragged through the streets of Baghdad by their opponents and mutilated.[104] The short-lived federation between Jordan and Iraq was abolished by King Hussein, following the coup in 1958.[102]

Qasim controlled Iraq through military rule and in 1958 began forcibly redistributing surplus land owned by some citizens.[106][107] The Iraqi state emblem under Qasim was largely based on the Mesopotamian symbol of Shamash, and avoided pan-Arab symbolism by incorporating elements of Socialist heraldry.[108] Under Qasim, freedom of religion was granted to religious minorities.[109][110] The early restrictions on the Jews were removed by the Qasim's government and Jews were re-integreated into society.[109] Qasim's political ideologies were based on Iraqi nationalism, instead of Arab nationalism and he refused to join Gamal Abdel Nasser's political union between Egypt and Syria, which was known as the United Arab Republic.

In 1959, Colonel Abd al-Wahab al-Shawaf led an uprising in Mosul against Qasim's government with the aim of joining the United Arab Republic, but was defeated by the government.[108] Iraq withdrew from the Baghdad Pact in 1959 leading to strained relations with the West and it developed a close alliance with the Soviet Union.[108][111] Qasim began claiming Kuwait as part of Iraq, when it was officially declared as an independent country in 1961.[111] During the Ottoman rule, Kuwait was part of Basra Province and was separated by the British, to establish the Kuwait protectorate.[111] In response, the United Kingdom sent its armed forces to the Iraq–Kuwait border and Qasim was forced to back down.[111]

In 1961, Kurdish nationalist movements, led by Mustafa Barzani's Kurdistan Democratic Party, launch an armed rebellion against the Iraqi government, seeking Kurdish autonomy.[108] The government faced challenges in quelling the Kurdish uprising, leading to intermittent conflict between Kurdish forces and the Iraqi military.[108] The armed rebellion escalated into war, which officially lasted for nine years until 1970.[108] Qasim was killed and overthrown by Colonel Abdul Salam Arif in a coup in February 1963, by members of the Ba'ath Party.[108] The Ba'ath Party assumed power, but internal divisions within the party lead to political instability and a series of unsuccessful coups, including the revolt at the Ar-Rashid army camp in Baghdad, which was crushed by the government.[112] After Abdul Salam Arif's death in a plane crash in 1966, he was succeeded by his brother, Abdul Rahman Arif.[112] Iraq sided with the Arab coalition and Palestine in Six-Day War against Israel in 1967.[108] Arif was overthrown in a coup d'état by the Ba'ath Party on 17 July 1968 and fled Iraq.[113][112]

Ba'athist Iraq

Following the coup d'état, the Ba'ath government formed and established Iraq as one party state, with Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr as president.[114] But the movement gradually came under Saddam Hussein, Iraq's vice-president and had de facto governance over the country.[114] He instituted socio-economic reforms,[115] including greatly improving Iraq's literacy levels and reducing income inequality.[114] Following the end of the First Iraqi–Kurdish War in 1970, a peace treaty was signed between the government and Mustafa Barzani, which granted autonomy to the Kurds.[116] The government's Arabization program in Kirkuk and disputes over revene-sharing sparked another war between Iraqi government and the Kurds in 1974.[117] The 1975 peace treaty between Iraq and Iran solved Shatt al-Arab dispute and as a result Iran withdrew support for the Kurdish rebels, resulting in their defeat to the government in 1975.[118][117]

Saddam was acceded to the presidency and control of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), then Iraq's supreme executive body in July 1979.[119] Meanwhile, the Islamic revolution in Iran shook the whole Middle East.[120] Iraq viewed the new Islamic Republic as threat.[120] Since Iraq had a Shi'ite majority and the new Islamic Republic would export Islamic revolution and Khomenist ideologies to Iraq, encouraging the Iraqi Shi'ite community to overthrow Saddam's Sunni-led government.[120] Following months of cross-border conflict with Iran, Saddam declared war on Iran and invaded in September 1980.[121] Taking advantage of the post-Iranian Revolution chaos in Iran, Iraq captured some territories in southwest Iran.[120] But Iran recaptured all of the lost territories within two years, and for the next six years Iran was on the offensive.[120] In 1981, Israel attacked and destroyed a nuclear reactor and tensions between Israel and Iraq increased.[122][120] Kurdish rebels launched a rebellion against the government from 1983 to 1986, which resulted 110,000 civilians being killed.[123] Baghdad, Kirkuk and Basra were bombed by the Iranian Armed forces.[120] The war, which ended in stalemate in 1988, killed between half a million and 1.5 million people.[124] During the war, Saddam Hussein extensively used chemical weapons against Iranians.[125] Iran suffered economic losses of $561 billion.[124] In the final stages of the war, the Iraqi regime launched the Al-Anfal Campaign against Kurdish rebels.[126][124] The campaign resulted in 50,000–100,000 civilians killed.[127][128][129] The Halabja massacre was the most notorious massacre during the campaign.[127] Other ethnic groups such as Yazidis, Shabaks and Mandaens were also targeted in the process.[127] According to several human rights organizations, this campaign constituted genocide.[127]

Due to Iraq's inability to pay Kuwait more than $14 billion that it had borrowed to finance the Iran–Iraq War and Kuwait's surge in petroleum production levels which kept revenues down, Iraq called Kuwait's refusal to decrease its oil production as an act of aggression.[130] In August 1990 Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait as its 19th governorate and established Free Kuwait Government.[130] This led to military intervention by United States-led coalition forces in the Gulf War.[130] The coalition forces proceeded with a bombing campaign targeting military targets and then launched an 100-hour-long ground assault against Iraqi forces in Southern Iraq and Kuwait, quickly overpowering and expelling Iraqi forces.[131][132][133] During the war, Iraq also launched scud missile attacks against Saudi Arabia and Israel.[134] Iraq's armed forces were devastated during the war.[133] The war resulted in the expulsion of many people from Kuwait.[131] Since then, relations between Iraq and the United States remained tense.[135] Shortly after the end of the war in February 1991, Kurds and Shi'ites launched several uprisings against Saddam's regime, but these were defeated.[136] It is estimated that as many as 100,000 people, including many civilians were killed.[136] During the uprisings the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Turkey, claiming authority under United States Security Council resolution 688, established the Iraqi no-fly zones to protect Kurdish population from attacks.[137] A civil war from 1994 to 1997 took place in the Kurdish region of Iraq, between rival factions of Patriotic Union of Kurdistan and the Kurdistan Democratic Party, with the later group supported by Saddam since 1995.[138] Between 35,000 and 40,000 fighters and civilians were killed.[138] During the 2001–2003 military conflict between the Kurdistan Regional Government and the Islamist militant group Ansar al-Islam, more than 300 people were killed.[139]

Iraq was ordered to destroy its chemical and biological weapons and the United Nations attempted to compel Saddam's government to disarm and agree to a ceasefire by imposing additional sanctions on the country in addition to the initial sanctions imposed following Iraq's invasion of Kuwait.[140] The Iraqi government's failure to disarm and agree to a ceasefire resulted in sanctions which remained in place until 2003.[141] The effects of the sanctions on the civilian population of Iraq have been disputed.[142][140] Whereas it was widely believed that the sanctions caused a major rise in child mortality, recent research has shown that commonly cited data were fabricated and that "there was no major rise in child mortality in Iraq".[143][144][145] An oil for food program was established in 1996 to ease the effects of sanctions.[146]

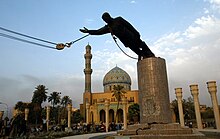

Iraq War and occupation

After the September 11 attacks, George W. Bush began planning the overthrow of Saddam in what is now widely regarded as a false pretense Saddam's Iraq was included in Bush's "axis of evil". The United States Congress passed joint resolution, which authorized the use of armed force against Iraq. In November 2002. The UN Security Council passed resolution 1441. On 20 March 2003, the United States-led coalition invaded Iraq, as part of global war on terror. Within weeks, coalition forces occupied much of Iraq, with the Iraqi Army adopting guerrilla tactics to confront coalition forces. Following the fall of Baghdad in first week of April, Saddam's regime had completely lost control of Iraq.[147] A statue of Saddam was toppled in Baghdad, symbolizing the end of his rule.[147]

The United States then established the Coalition Provisional Authority to govern Iraq.[147] In May 2003, L. Paul Bremer, the chief executive of the CPA, issued orders to exclude Ba'ath Party members from the new Iraqi government and to disband the largely Sunni Iraqi Army.[148] The decision excluded many of the country's former government officials.[149] 40,000 school teachers who had joined the Ba'ath Party were also fired,[148] helping to bring about a chaotic post-invasion environment, including increased archaeological looting. The Jewish Archive of Iraq was found in Saddam's intelligence headquarters.[150]

An insurgency against the coalition forces began in summer 2003, including in Baghdad, Fallujah and Basra, which included elements of the former Iraqi secret police and army.[147] Various extremist Sunni militants groups were created in 2003, for example Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. They began targeting coalition forces.[147] The insurgency included widespread sectarian violence between Sunnis and Shias.[151] The coalition forces began capturing members of the Ba'ath Party. Over 300 top Ba'athist leaders were killed or captured by the coalition forces. Uday and Qusay Hussein were killed by the coalition forces in July 2003. Saddam Hussein was captured in December 2003. The Mahdi Army—a Shia militia created in the summer of 2003 by Muqtada al-Sadr—began to fight Coalition forces in April 2004.[152]

There was increased fighting between Sunni and Shia militants in 2004. Insurgents also fought against the new Iraqi Interim Government which was established in June 2004.[147] Insurgents fought coalition forces in the first and second battles of Fallujah in April and November 2004.[147] The Mahdi army would kidnap and kill Sunni civilians as part of a campaign that has been described as genocide.[153] Coalition forces received heavy criticism for various war crimes committed throughout the war, including the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse,[147][154] the Mukaradeeb wedding party massacre.[155][156] the Haditha massacre, and the Mahmudiyah rape and killings.[157][158][159]

Sectarian violence between Shi'as and Sunnis escalated into civil war, which lasted from 2006 to 2008. In late 2006, the US government's Iraq Study Group recommended that the US begin focusing on training Iraqi military personnel and in January 2007 US President George W. Bush announced a "Surge" in the number of US troops deployed to the country. During 2006, fighting continued and reached its highest levels of violence. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq was killed by the coalition forces in June 2006.[160] Saddam Hussein was convicted of crimes against humanity related to the 1982 Dujail massacre and executed in December 2006.[161] Thousands of sectarian bombings and attacks occurred during the war. The deadliest bombing of the war occurred in August 2007 in Yazidi towns of Nineveh Governorate, where 700 people were killed.[162] In 2008, fighting continued and Iraq's newly trained armed forces launched an offensive against militants.

On the morning of 18 December 2011, the final contingent of US troops ceremonially exited over the border to Kuwait.[19] Crime and violence initially spiked in the months following the U.S. withdrawal from cities in mid-2009[163][164] but despite the initial increase in violence, in November 2009, Iraqi Interior Ministry officials reported that the civilian death was the lowest level since the 2003 invasion.[165][166] Violence against the religious minorities of Iraq at the hands of insurgents, including Christians, Mandeans, Yazidis and Jews was commonplace during the war.[167] The main rationale for the invasion based on the claim that Iraq was pursuing weapons of mass destruction was based on documents provided by the CIA and the British government that were later found to be unreliable.[168][169][170] Allegations on Saddam having links with Al-Qaeda was also found to be false.[168][169][170] Following the withdrawal of US troops in 2011, the insurgency continued and Iraq suffered from political instability.[171] The continued instability in Iraq has improved Saddam Hussein's reputation.[171] It has been argued that the United States invasion was actually aimed at expanding its spheres of influence.[172] The Iraq war between 2003 and 2011 resulted in between 151,000 and 1.2 million Iraqis killed.[173][174]

Post-war conflict and insurgency

Sectarian violence continued in the first half of 2013 with at least 56 people killed in April when a Sunni protest in Hawija was interrupted by a government-supported helicopter raid. On 20 May 2013, at least 95 people died in a wave of car bomb attacks that was preceded by a car bombing on 15 May that led to 33 deaths; also, on 18 May, 76 people were killed in the Sunni areas of Baghdad.[175][176] On 22 July 2013, at least five hundred convicts, many of whom were senior members of Al-Qaeda, were freed from Abu Ghraib prison during an attack by Al-Qaeda.[177] James F. Jeffrey, the United States ambassador to Iraq in 2011, said the escape "will provide seasoned leadership and a morale boost to Al Qaeda and its allies in both Iraq and Syria".[178]

By late June, the Iraqi government had lost control of its borders with both Jordan and Syria.[179] al-Maliki called for a national state of emergency on 10 June following the attack on Mosul. However, Iraq's parliament did not allow Maliki to declare a state of emergency; many legislators boycotted as they opposed expanding the prime minister's powers.[180] After an inconclusive election in April 2014, Nouri al-Maliki served as caretaker-Prime-Minister.[181] On 11 August, Iraq's highest court ruled that PM Maliki's bloc was the largest in parliament, meaning Maliki could continue as Prime Minister.[181] By 13 August, however, the Iraqi president had tasked Haider al-Abadi with forming a new government, and the United Nations, the U.S., the European Union, Saudi Arabia, Iran expressed their wish for new leadership in Iraq.[182] On 14 August, Maliki stepped down as PM.[183][184] On 8 September 2014, Haider al-Abadi became prime minister.[185] Abadi promised to stamp out corruption and ease sectarian tensions.[186]

In response to rapid territorial gains made by the Islamic State in early 2014, and its universally-condemned executions and human rights abuses, many states intervened in Iraq against ISIS in the 2013–2017 war. ISIL began losing ground in both Iraq and Syria.[187] Tens of thousands of civilians have been killed in Iraq in ISIL-linked violence.[188][189] The genocide of Yazidis by ISIL led to thousands killed and the effective exile of the Yazidis.[190] The 2016 Karrada bombing killed nearly 400 civilians and injured hundreds more.[191] The 2017 battle of Mosul resulted in thousands killed and the recapture of the city from ISIS by the Iraqi government, supported by coalition forces.[192] By December 2017, ISIL had no remaining territory in Iraq, following the 2017 Western Iraq campaign.[193]

On 9 December 2017, then-Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi declared victory over ISIL and announced full liberation of borders with Syria from Islamic State militants.[194] Kirkuk's control were taken by the Iraqi government, following the 2017 battle. Parliamentary elections were held on 12 May 2018.[195] Kurdish politician, Barham Salih was elected as president by parliament in October 2018.[196] Former Finance Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi was selected to form a new government. The new government was approved by the Council of Representatives on 24 October 2018.[195][197] Protests over deteriorating economic conditions and state corruption started in July 2018 in Baghdad and other major Iraqi cities, mainly in the central and southern provinces.

The nationwide protests, erupting in October 2019, led to the deaths of 93 people.[198] In 2020, a U.S. drone strike killed Qasem Soleimani, leader of Iran's Quds Force, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, deputy commander of the Popular Mobilization Forces, as their convoy left Baghdad Airport.[199] Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi survived a failed assassination attempt in November 2021.[200] Muqtada al-Sadr's Sadrist Movement was the biggest winner in 2021 parliamentary elections.[201] Governmental stalemate lead to the 2022 Iraqi political crisis.[202] In October 2022, Abdul Latif Rashid was elected as the new president after winning the parliamentary election against incumbent Barham Salih, who was running for a second term.[203] In 2022, Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, close ally of former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, took the office to succeed Mustafa al-Kadhimi as new Prime Minister.[204]

The country's electrical grid faces systemic pressures due to climate change, fuel shortages, and an increase in demand.[205][206] Corruption remains endemic throughout all levels of Iraqi governance while the political system has exacerbated sectarian conflict.[207][208] Climate change is driving wide-scale droughts across the country while water reserves are rapidly depleting.[209] The country has been in a prolonged drought since 2020 and experienced its second-driest season in the past four decades in 2021. Water flows in the Tigris and Euphrates are down between 30 and 40%. Half of the country's farmland is at risk of desertification.[210] Nearly 40% of Iraq "has been overtaken by blowing desert sands that claim tens of thousands of acres of arable land every year".[211]

Geography

Iraq lies between latitudes 29° and 38° N, and longitudes 39° and 49° E (a small area lies west of 39°). Spanning 437,072 km2 (168,754 sq mi), it is the 58th-largest country in the world.

It has a coastline measuring 58 km (36 miles) on the northern Persian Gulf.[212] Further north, but below the main headwaters only, the country easily encompasses the Mesopotamian Alluvial Plain. Two major rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, run south through Iraq and into the Shatt al-Arab, thence the Persian Gulf. Broadly flanking this estuary (known as arvandrūd: اروندرود among Iranians) are marshlands, semi-agricultural. Flanking and between the two major rivers are fertile alluvial plains, as the rivers carry about 60,000,000 m3 (78,477,037 cu yd) of silt annually to the delta.

The central part of the south, which slightly tapers in favour of other countries, is natural vegetation marsh mixed with rice paddies and is humid, relative to the rest of the plains.[citation needed] Iraq has the northwestern end of the Zagros mountain range and the eastern part of the Syrian Desert.[citation needed]

Rocky deserts cover about 40 percent of Iraq. Another 30 percent is mountainous with bitterly cold winters. The north of the country is mostly composed of mountains; the highest point being at 3,611 m (11,847 ft). Iraq is home to seven terrestrial ecoregions: Zagros Mountains forest steppe, Middle East steppe, Mesopotamian Marshes, Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests, Arabian Desert, Mesopotamian shrub desert, and South Iran Nubo-Sindian desert and semi-desert.[213]

Climate

Much of Iraq has a hot arid climate with subtropical influence. Summer temperatures average above 40 °C (104 °F) for most of the country and frequently exceed 48 °C (118.4 °F). Winter temperatures infrequently exceed 15 °C (59.0 °F) with maxima roughly 5 to 10 °C (41.0 to 50.0 °F) and night-time lows 1 to 5 °C (33.8 to 41.0 °F). Typically, precipitation is low; most places receive less than 250 mm (9.8 in) annually, with maximum rainfall occurring during the winter months. Rainfall during the summer is rare, except in northern parts of the country.

The northern mountainous regions have cold winters with occasional heavy snows, sometimes causing extensive flooding.[citation needed] Iraq is highly vulnerable to climate change.[214] The country is subject to rising temperatures and reduced rainfall, and suffers from increasing water scarcity for a human population that rose tenfold between 1890 and 2010 and continues to rise.[215][216]

Biodiversity

The wildlife of Iraq includes its flora and fauna and their natural habitats.[218] Iraq has multiple and diverse biomes which include the mountainous region in the north to the wet marshlands along the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, while western part of the country comprises mainly desert and some semi-arid regions. Many of Iraq's bird species were endangered, including seven of Iraq's mammal species and 12 of its bird species. The Mesopotamian marches in the middle and south are home to approximately 50 species of birds, and rare species of fish. At risk are some 50% of the world's marbled teal population that live in the marshes, along with 60% of the world's population of Basra reed-warbler.[219]

Draining of the Mesopotamian Marshes, by Saddam's regime, caused there a significant drop in biological life. Since the overthrow, flow is restored and the ecosystem has begun to recover.[220] Iraqi corals are some of the most extreme heat-tolerant as the seawater in this area ranges between 14 and 34 °C.[221] Aquatic or semi-aquatic wildlife occurs in and around these, the major lakes are Lake Habbaniyah, Lake Milh, Lake Qadisiyah and Lake Tharthar.[222]

Government and politics

The federal government of Iraq is defined under the current Constitution as a democratic, federal parliamentary republic. The federal government is composed of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, as well as numerous independent commissions. Aside from the federal government, there are regions (made of one or more governorates), governorates, and districts within Iraq with jurisdiction over various matters as defined by law.[45]

The National Alliance is the main Shia parliamentary bloc, and was established as a result of a merger of Prime Minister Nouri Maliki's State of Law Coalition and the Iraqi National Alliance.[223] The Iraqi National Movement is led by Iyad Allawi, a secular Shia widely supported by Sunnis. The party has a more consistent anti-sectarian perspective than most of its rivals.[223] The Kurdistan List is dominated by two parties, the Kurdistan Democratic Party led by Masood Barzani and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan headed by Jalal Talabani. Both parties are secular and enjoy close ties with the West.[223] Baghdad is Iraq's capital, home to the seat of government. Located in the Green Zone, which contains governmental headquarters and the army, in addition to containing the headquarters of the American embassy and the headquarters of foreign organizations and agencies for other countries.

According to the 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Iraq was the third most electoral democratic country in the Middle East.[224] In 2023, according to the Fragile States Index, Iraq was the world's 27th most politically unstable country.[225] Transparency International ranks Iraq's government as the 23rd most corrupt government in the world.[226] Under Saddam Hussein, the government employeed 1 million employees, but this increased to around 7 million in 2016. In combination with decreased oil prices, the government budget deficit is near 25% of GDP as of 2016[update].[227] In September 2017, a referendum was held regarding Kurdish independence in Iraq. 92% of Iraqi Kurds voted in favor of independence.[228] The referendum was regarded as illegal by the federal government.[229] Kurdistan Regional Government have announced that it would respect the Supreme Federal Court's ruling that no Iraqi province is allowed to secede.[230]

Law

In October 2005, the new Constitution of Iraq was approved in a referendum with a 78% overall majority, although the percentage of support varied widely between the country's territories.[231] The new constitution was backed by the Shia and Kurdish communities, but was rejected by Arab Sunnis. Under the terms of the constitution, the country conducted fresh nationwide parliamentary elections on 15 December 2005. All three major ethnic groups in Iraq voted along ethnic lines, as did Assyrian and Turcoman minorities. Law no. 188 of the year 1959 (Personal Status Law)[232] made polygamy extremely difficult, granted child custody to the mother in case of divorce, prohibited repudiation and marriage under the age of 16.[233] Article 1 of Civil Code also identifies Islamic law as a formal source of law.[234] Iraq had no Sharia courts but civil courts used Sharia for issues of personal status including marriage and divorce. In 1995 Iraq introduced Sharia punishment for certain types of criminal offences.[235] The code is based on French civil law as well as Sunni and Jafari (Shi'ite) interpretations of Sharia.[236]

In 2004, the CPA chief executive L. Paul Bremer said he would veto any constitutional draft stating that sharia is the principal basis of law.[237] The declaration enraged many local Shia clerics,[238] and by 2005 the United States had relented, allowing a role for sharia in the constitution to help end a stalemate on the draft constitution.[239] The Iraqi Penal Code is the statutory law of Iraq.

Military

Iraqi security forces are composed of forces serving under the Ministry of Interior (MOI) and the Ministry of Defense (MOD), as well as the Iraqi Counter Terrorism Bureau, reporting directly to the Prime Minister of Iraq, which oversees the Iraqi Special Operations Forces. MOD forces include the Iraqi Army, the Iraqi Air Force, Iraqi Navy and Peshmerga, which, along with their security subsidiaries, are responsible for the security of the Kurdistan Region.[240] The MOD also runs a Joint Staff College, training army, navy, and air force officers, with support from the NATO Training Mission - Iraq. The college was established at Ar Rustamiyah on 27 September 2005.[241] The center runs Junior Staff and Senior Staff Officer Courses designed for first lieutenants to majors.

The current Iraqi armed forces was rebuilt on American foundations and with huge amounts of American military aid at all levels. The army consists of 13 infantry divisions and one motorised infantry. Each division consists of four brigades and comprises 14,000 soldiers. Before 2003, Iraq was mostly equipped with Soviet-made military equipment, but since then the country has turned to Western suppliers.[242] The Iraqi air force is designed to support ground forces with surveillance, reconnaissance and troop lift. Two reconnaissance squadrons use light aircraft, three helicopter squadrons are used to move troops and one air transportation squadron uses C-130 transport aircraft to move troops, equipment, and supplies. The air force currently has 5,000 personnel.[243]

As of February 2011, the navy had approximately 5,000 sailors, including 800 marines. The navy consists of an operational headquarters, five afloat squadrons, and two marine battalions, designed to protect shorelines and inland waterways from insurgent infiltration. On 4 November 2019, more than 100 Australian Defence Force personnel left Darwin for the 10th rotation of Task Group Taji, based north of Baghdad. The Australian contingent mentors the Iraqi School of Infantry, where the Iraqi Security Forces are trained. However, Australia's contribution was reduced from 250 to 120 ADF personnel, which along with New Zealand had trained over 45,000 ISF members before that.[244]

Foreign relations

The Ba'athist period, Iraq maintained close ties with pro-Soviet countries.[245] Under Saddam, Iraq was a strong ally of India in the Middle East.[246] During the Vietnam War, Saddam provided financial assistance to North Vietnam and even refused to ask for repaying the amount of the financial assistance. This move is respected even by his opponents.[247] After the end of the Iraq War, Iraq sought and strengthened regional economic cooperation and improved relations with neighboring countries.[248] On 12 February 2009, Iraq officially became the 186th State Party to the Chemical Weapons Convention. Under the provisions of this treaty, Iraq is considered a party with declared stockpiles of chemical weapons. Because of their late accession, Iraq is the only State Party exempt from the existing timeline for destruction of their chemical weapons.[249]

Since the situation eased, Iraq re-engaged with its Arab neighbors while maintaining relations with Iran in an attempt to position Iraq as a country that would not exacerbate the security concerns of its neighbors and seeking a pragmatic balance in foreign relations.[248] Iran–Iraq relations have flourished since 2005 by the exchange of high-level visits.[248] A conflict occurred in December 2009, when Iraq accused Iran of seizing an oil well on the border.[250] Relations with Turkey are tense, largely because of the Kurdistan Regional Government, as clashes between Turkey and the PKK continue.[251] In October 2011, the Turkish parliament renewed a law that gives Turkish forces the ability to pursue rebels over the border in Iraq.[252] Turkey's "Great Anatolia Project" reduced Iraq's water supply and affected agriculture.[253][216] Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani has sought to normalise relations with Syria in order to expand co-operation.[254] Iraq is also seeking to deepen its ties with the Gulf Cooperation Council countries.[255] Roreign ministers of Iraq and Kuwait have announced that they were working on a definitive agreement on border demarcation.[256][257]

.jpg/220px-President_Obama_Addresses_the_Leaders%27_Summit_to_Counter_ISIL_and_Violent_Extremism_at_UN_Headquarters_in_New_York_City_(21634567340).jpg)

On 17 November 2008, the US and Iraq agreed to a Status of Forces Agreement,[258] as part of the broader Strategic Framework Agreement.[259] On 5 January 2020, the Iraqi parliament voted for a resolution that urges the government to work on expelling US troops from Iraq. The resolution was passed two days after a US drone strike that killed Iranian Major General Qasem Soleimani of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, commander of the Quds Force. The resolution specifically calls for ending of a 2014 agreement allowing Washington to help Iraq against Islamic State groups by sending troops.[260] This resolution will also signify ending an agreement with Washington to station troops in Iraq as Iran vows to retaliate after the killing.[261] On 28 September 2020, Washington made preparations to withdraw diplomats from Iraq, as a result of Iranian-backed militias firing rockets at the American Embassy in Baghdad. The officials said that the move was seen as an escalation of American confrontation with Iran.[262] The United States significantly reduced its military presence in Iraq after the defeat of ISIS.[263]

Human rights

Relations between Iraq and its Kurdish population have been sour in recent history, especially with Saddam Hussein's genocidal campaign against them in the 1980s. After uprisings during the early 90s, many Kurds fled their homeland and no-fly zones were established in northern Iraq to prevent more conflicts. Despite historically poor relations, some progress has been made, and Iraq elected its first Kurdish president, Jalal Talabani, in 2005. Furthermore, Kurdish is now an official language of Iraq alongside Arabic according to Article 4 of the Constitution.[45]

LGBT rights in Iraq remain limited. Although decriminalised, homosexuality remains stigmatised in Iraqi society.[264] Human rights in Islamic State-controlled territory have been recorded as highly violated. It included mass executions in Islamic State-occupied part of Mosul and genocide of the Yazidis in Yazidi populated Sinjar, which is in northern Iraq.[265]

Administrative divisions

Iraq is composed of eighteen governorates (or provinces) (Arabic: muhafadhat (singular muhafadhah)). The governorates are subdivided into districts (or qadhas), which are further divided into sub-districts (or nawāḥī). A nineteenth governorate, Halabja Governorate, is unrecognised by the Iraqi government.

Economy

Iraq's economy is dominated by the oil sector, which has traditionally provided about 95% of foreign exchange earnings. The lack of development in other sectors has resulted in 18%–30% unemployed and a per capita GDP of $4,812.[3] Public sector employment accounted for nearly 60% of full-time employment in 2011.[266] The oil export industry, which dominates the Iraqi economy, generates very little employment.[266] Currently only a modest percentage of women (the highest estimate for 2011 was 22%) participate in the labour force.[266]

Prior to US occupation, Iraq's centrally planned economy prohibited foreign ownership of Iraqi businesses, ran most large industries as state-owned enterprises, and imposed large tariffs to keep out foreign goods.[267] After the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Coalition Provisional Authority quickly began issuing many binding orders privatising Iraq's economy and opening it up to foreign investment. On 20 November 2004, the Paris Club of creditor nations agreed to write off 80% ($33 billion) of Iraq's $42 billion debt to Club members. Iraq's total external debt was around $120 billion at the time of the 2003 invasion, and had grown another $5 billion by 2004. The debt relief was to be implemented in three stages: two of 30% each and one of 20%.[268] The official currency in Iraq is the Iraqi dinar. The Coalition Provisional Authority issued new dinar coins and notes, with the notes printed by De La Rue using modern anti-forgery techniques.[269] Jim Cramer's 20 October 2009 endorsement of the Iraqi dinar on CNBC has further piqued interest in the investment.[270]

Five years after the invasion, an estimated 2.4 million people were internally displaced (with a further two million refugees outside Iraq), four million Iraqis were considered food-insecure (a quarter of children were chronically malnourished) and only a third of Iraqi children had access to safe drinking water.[271] In 2022, and after more than 30 years after the UN Compensation Commission (UNCC) was created to ensure restitution for Kuwait following the Iraqi invasion of 1990, the reparations body announced that Iraq has paid a total of $52.4 billion in war reparations to Kuwait.[272] According to the Overseas Development Institute, international NGOs face challenges in carrying out their mission, leaving their assistance "piecemeal and largely conducted undercover, hindered by insecurity, a lack of coordinated funding, limited operational capacity and patchy information".[271] International NGOs have been targeted and during the first 5 years, 94 aid workers were killed, 248 injured, 24 arrested or detained and 89 kidnapped or abducted.[271]

Tourism

Iraq was an important tourist destination for many years but that changed dramatically during the war with Iran and after the 2003 invasion by US and allies.[273] As Iraq continues to develop and stabilises, the tourism in Iraq is still facing many challenges, little has been made by the government to meet its tremendous potential as a global tourist destination, and gain the associated economic benefits, mainly due to conflicts.[274] Sites from Iraq's ancient past are numerous and many that are close to large cities have been excavated. Babylon has seen major recent restoration; known for its famous Ziggurat (the inspiration for the Biblical Tower of Babel), the Hanging Gardens (one of the Seven Wonders of the World), and the Ishtar Gate, making it a prime destination.

Nineveh, a rival to Babylon, has also seen significant restoration and reconstruction. Ur, one of the first Sumerian cities, which is near Nasiriyya, has been partially restored. This is a list of examples of some significant sites in a country with a tremendous archaeological and historic wealth.[275] Iraq is considered to be a potential location for ecotourism.[276] The tourism in Iraq includes also making pilgrimages to holy Shia sites near Karbala and Najaf. Mosul Museum is the second largest museum in Iraq after the Iraq Museum in Baghdad. It contains ancient Mesopotamian artifacts.

Saddam Hussein built hundreds of palaces and monuments across the country. Some of them include Al-Faw Palace, Republican Palace, As-Salam Palace and Radwaniyah Palace.[277] Al-Faw Palace was constructed to commemorate Iraqi soldiers who were successful in re-taking the Al-Faw peninsula during the 1980–1988 Iran–Iraq War. Currently it is occupied by the American University of Iraq. Since Saddam's overthrow, the palaces are open to tourists, though they are not officially functioning, and the government of Iraq is considering to sell them for useful purposes. A majority of these structures were built after the 1991 Gulf War, when Iraq was put under sanctions by the United Nations.[277] Saddam Hussein reconstructed part of Babylon, one of the world's earliest cities, using bricks inscribed with his name to associate himself with the region's past glories.[278] One of his palaces in Basra was turned into a museum, despite it was time when Iraq allied with the United States was engaged in war with the ISIS.[279][clarification needed]

Transport

Iraq has a modern network of highways. Roadways extended 45,550 km (28,303 mi).[280] The roadway also connect Iraq to neighboring countries of Iran, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait.[280] There are more than seven million passenger cars, over million commercial taxis, buses, and trucks in use. On major highways the maximum speed is 110 km/h (68 mph).[281] Iraq has about 104 airports as of 2012. Major airports include Baghdad International Airport, Basra International Airport, Mosul International Airport, Erbil International Airport, Sulaimaniyah International Airport and Najaf International Airport.

Oil and energy

.jpg/220px-Al_Basrah_Oil_Terminal_(ABOT).jpg)

With its 143.1 billion barrels (2.275×1010 m3) of proved oil reserves, Iraq ranks third in the world behind Venezuela and Saudi Arabia in the amount of oil reserves.[282][283] Oil production levels reached 3.4 million barrels per day by December 2012.[284] Only about 2,000 oil wells have been drilled in Iraq, compared with about 1 million wells in Texas alone.[285] Iraq was one of the founding members of OPEC.[286][287]

During the 1970s Iraq produced up to 3.5 million barrels per day, but sanctions imposed against Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait in 1990 crippled the country's oil sector. The sanctions prohibited Iraq from exporting oil until 1996 and Iraq's output declined by 85% in the years following the First Gulf War. The sanctions were lifted in 2003 after the US-led invasion removed Saddam Hussein from power, but development of Iraq's oil resources has been hampered by the ongoing conflict.[288] As of 2010[update], despite improved security and billions of dollars in oil revenue, Iraq still generates about half the electricity that customers demand, leading to protests during the hot summer months.[289] The Iraq oil law, a proposed piece of legislation submitted to the Council of Representatives of Iraq in 2007, has failed to gain approval due to disagreements among Iraq's various political blocs.[290][291] Al Başrah Oil Terminal is a trans-shipment facility from the pipelines to the tankers and uses supertankers.

According to a US Study from May 2007, between 100,000 barrels per day (16,000 m3/d) and 300,000 barrels per day (48,000 m3/d) of Iraq's declared oil production over the past four years could have been siphoned off through corruption or smuggling.[292] In 2008, Al Jazeera reported $13 billion of Iraqi oil revenues in US care was improperly accounted for, of which $2.6 billion is totally unaccounted for.[293] Some reports that the government has reduced corruption in public procurement of oil; however, reliable reports of bribery and kickbacks to government officials persist.[294]

On 30 June and 11 December 2009, the Iraqi ministry of oil awarded service contracts to international oil companies for some of Iraq's many oil fields.[295][296] Oil fields contracted include the "super-giant" Majnoon oil field, Halfaya Field, West Qurna Field and Rumaila Field.[296] BP and China National Petroleum Corporation won a deal to develop Rumaila, the largest Iraqi oil field.[297][298] On 14 March 2014, the International Energy Agency said Iraq's oil output jumped by half a million barrels a day in February to average 3.6 million barrels a day. The country had not pumped that much oil since 1979, when Saddam Hussein rose to power.[299] However, on 14 July 2014, as sectarian strife had taken hold, Kurdistan Regional Government forces seized control of the Bai Hassan and Kirkuk oilfields in the north of the country, taking them from Iraq's control. Baghdad condemned the seizure and threatened "dire consequences" if the fields were not returned.[300] On 2018, the UN estimated that oil accounts for 99% of Iraq's revenue.[288] As of 2021, the oil sector provided about 92% of foreign exchange earnings.[301]

Water supply and sanitation

Three decades of war greatly cut the existing water resources management system for several major cities. This prompted widespread water supply and sanitation shortfalls thus poor water and service quality.[216] This is combined with few businesses and households who are fully environmentally aware and legally compliant however the large lakes, as pictured, alleviate supply relative to many comparators in Western Asia beset by more regular drought. Access to potable water diverges among governorates and between urban and rural areas. 91% of the population has access to potable water. Forming this figure: in rural areas, 77% of people have access to improved (treated or fully naturally filtered) drinking water sources; and 98% in urban areas.[302] Much water is discarded during treatment, due to much outmoded equipment, raising energy burden and reducing supply.[302]

Infrastructure

Although many infrastructure projects had already begun, at the end of 2013 Iraq had a housing crisis. The then very war-ravaged country was set to complete 5 percent of the 2.5 million homes it needs to build by 2016 to keep up with demand, confirmed the Minister for Construction and Housing.[303] In 2009, the Iraq Britain Business Council formed. Its key impetus was House of Lords member and trade expert Lady Nicholson. In mid 2013, South Korean firm Daewoo reached a deal to build Bismayah New City of about 600,000 residents in 100,000 homes.[304]

.jpg/220px-Mosque_-_panoramio_(6).jpg)

In December 2020, the Prime Minister launched the second phase of the Grand Faw Port via winning bid of project manager/head contractor Daewood at $2.7 billion.[305] In late 2023, the Iraqi government announced that it will build a total of 15 new cities across the country, in an attempt to tackle a persistent housing problem, according to officials.[306] In addition, This project falls under the Iraqi government's plan and strategy to establish new residential cities outside city centers, aiming to alleviate the urban housing crisis. The first 5 new cities cities will be located in Baghdad, Babylon, Nineveh, Anbar and Karbala, while another 10 new residential cities will be launched in other governorates. The initial phase of the [housing] plan began in late 2023, when Iraqi Prime Minister, Al-Sudani laid the foundaton stone of Al-Jawahiri city. Located in west of the capital, the new city will host 30,000 housing units which will cost $2 billion. It is expected to be completed in four to five years. According to officials, none of it financed by the government.[307][308][309]

In early 2024, the Iraqi government signed a contract for the new Ali El-Wardi residential city project with the director of Ora Real Estate Development Company, Naguib Sawiris, which is the largest project among the five new residential city projects in its first phase.[310] Located east of Baghdad, the city will offer over 100,000 residential units. First of its kind in the country, the city will specialize in providing advanced technological infrastructure for smart cities and will match up to the highest sustainability standards.[311] The goal for the Iraqi government is to build 250,000 to 300,000 housing units for poor and middle-class families and address a housing crisis, In addition, the cities will include universities, commercial centers, schools and health centers.[308] In 2024, and during a visit to Baghdad by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, quadrilateral memorandum of understanding regarding cooperation in Iraq Development Road project signed between Iraq, Türkiye, Qatar, UAE. The deal was inked by the transportation ministers from each country. The 1,200-kilometer project with railway and highways which will connect the Grand Faw Port, aimed to be the largest port in the Middle East. It is planned to be completed by 2025 to the Turkish border at an expected cost of $17 billion. According to Iraqi officials, the Development Road is a strategic national project for Iraq, and will become the largest sea port in the Middle East, as such strengthening Iraq's geopolitical position.[312][313][314]

Demographics

The 2021 estimate of the total Iraqi population is 43,533,592.[315][316] Iraq's population was estimated to be 2 million in 1878.[317] In 2013 Iraq's population reached 35 million amid a post-war population boom.[318] Those three vilayets of the Ottoman Empire — Mosul, Basra and Baghdad, where designated as concentration of different ethnic groups. Basra region borders Iran and is home to Shia Arabs. The Mosul region historically had a significant Assyrian population before the Islamic State in 2014, and borders areas where there are currently large Kurdish populations as well. The region around Baghdad is home to Sunni Arabs.

Ethnic groups

Iraq's native population is predominantly Arab, but also includes other ethnic groups such as Kurds, Turkmens, Assyrians, Yazidis, Shabaks, Armenians, Mandaeans, Circassians, and Kawliya.

A report by the European Parliamentary Research Service suggests that, in 2015, there were 24 million Arabs (14 million Shia and 9 million Sunni); 4.7 million Sunni Kurds (plus 500,000 Faili Kurds and 200,000 Kaka'i); 3 million (mostly Sunni) Iraqi Turkmens; 1 million Black Iraqis; 500,000 Christians (including Assyrians and Armenians); 500,000 Yazidis; 250,000 Shabaks; 50,000 Roma; 3,000 Mandaeans; 2,000 Circassians; 1,000 of the Baháʼí Faith; and a few dozen Jews.[319]